The Coyote (canis latrans)

Physical Description

Slimmer and smaller than the wolf, the male coyote weighs from 9 to 23 kg, has an overall length of 120 to 150 cm (including a 30- to 40-cm tail), and stands 58 to 66 cm high at the shoulder. The female is usually four-fifths as large.

The coyote’s ears are wide, pointed, and erect. It has a tapering muzzle and a black nose. Unlike most dogs, the top of the muzzle on coyotes forms an almost continuous line with the forehead. The yellow, slightly slanting eyes, with their black round pupils, give the coyote a characteristic expression of cunning. The canine, or pointed, teeth are remarkably long and can inflict serious wounds. The neck is well furred and looks oversized for the body. The long tongue often hangs down between the teeth; the coyote regulates its body temperature by panting.

The paw, more elongated than that of a dog of the same size, has four toes with nonretractable claws. The forepaws show a rudimentary thumb, reduced to a claw, located high on the inner side. The claws are not used in attack or defence; they are typically blunted from constant contact with the ground and do not leave deep marks.

The fur is generally a tawny grey, darker on the hind part of the back where the black-tipped hair becomes wavy. Legs, paws, muzzle, and the back of the ears are more yellowish in colour; the throat, belly, and the insides of the ears are whiter. The tail, darker on top and lighter on the underside, is lightly fawn-coloured towards the tip, which is black.

The coyote’s fur is long and soft and well suited to protect it from the cold. Because it is light-coloured in winter and dark in summer, it blends well with the seasonal surroundings.

Like all Canidae, the coyote has, at the root of the tail, a gland that releases a scent. Such glands also exist on other parts of the body. Scent glands often become more active when the animals meet. The coyote’s urine has a very strong smell and is used to mark out its territory. Trappers use the secretions when they set traps to attract the coyote.

Signs and Sounds

Like the wolf, the coyote’s best-known trait is its yelping and howling cry, a sequence of high-pitched, ear-piercing bayings. The coyote can also bark, growl, wail, and squeal. Although often silent in daytime, it may make itself heard at any time from sunset to sunrise, and especially at dusk and dawn.

If several coyotes are in the same vicinity, the howling of one triggers that of the others, resulting in an impressive concert. Two coyotes howling in unison can create the illusion of a dozen or more. The coyote can also sound farther away than it is.

Scientists are intrigued by the coyote’s howling, which seems to be a means of communication. The cry invariably brings a reply, then a sort of commentary followed by another prolonged cry, and finally a volley of raucous yelpings. Is it a cry for food, for a mate, or a proclamation of its territorial claims? Is it just an expression of joy at being alive or of sociability? The coyote is fond of playing with other coyotes, even with its prey before devouring it.

Habitat and Habits

European settlers found the coyote on the plains, prairies, and deserts of central and western North America. It appeared to prefer open or semi-wooded habitats. However, about the turn of the twentieth century, the coyote began a dramatic range expansion that is still in progress.

The reasons for the coyote’s expansion are not fully understood but probably include several conditions created by people: the clearing of forests, provision of carrion, or dead animal flesh, from domestic livestock, and the removal of the wolf. The mosaic of grassy fields, brush, and woodlots created by farming areas that were once covered with unbroken forest has provided attractive habitat for the coyote, as well as several other species like the red fox and raccoon.

The coyote has learned to scavenge the carcasses of domestic livestock, much as it still scavenges the carrion left by wolves, where the two species occur together. The removal of the wolf in some areas has meant more to coyotes than the absence of a feared predator. It has meant less competition for many prey animals. For example, in winter, when snow conditions are right, coyotes can kill large ungulates, or hoofed mammals, such as deer, that multiply in the absence of wolves. Also, in hard winters, when these swollen deer populations run out of food, the deer die of starvation, and the resident coyotes enjoy a food bonanza.

The coyote is one of North America’s most controversial animals. It is intelligent and playful, like many domestic dogs, but it is also a predator with a reputation for killing small farm animals.

The name coyote is a Spanish alteration of the original Aztec name coyotl. The Latin name Canis latrans, meaning barking dog, was given to it by Thomas Say, who published a description of the species in 1833. Since 1967, its official name in Canada, in both English and French, has been coyote. In some parts of Canada coyotes are called "brush wolves." Wolves are much larger and characteristically hunt in packs.

Unique Characteristics

The coyote’s senses of hearing and smell are so well developed that a sudden odour or noise can make it change its course in mid-step. Its agility in this respect is incredible, perhaps unique in the animal kingdom.

The coyote is a remarkably hard runner, galloping along at 40 km per hour, but capable of reaching 64 km per hour. Greyhounds, well known for their speed in running, can catch up with coyotes, but may require quite a long time to do so. If the need arises, the coyote can swim well.

Swift, tough, and wily, the coyote is the best challenge a hunter could wish for. It has only two known weaknesses: it sleeps heavily and looks back while fleeing. It sleeps deeply enough to be approached closely, but the problem is to do so noiselessly because the coyote often beds down in thickets. It also becomes an easy target when it turns while fleeing to look back; it will stop just moments after being shot at to measure its headway over its pursuer. If the hunter is ready, this glance may be the animal’s last.

Range

Smaller than a wolf, and more adaptable, the coyote is one of the few mammals whose range is increasing, despite extensive persecution by people.

In Canada, the coyote still inhabits its traditional habitats, the aspen parkland and short- and mixed-grass prairie in the three prairie provinces. However, it has spread north into the boreal forest, west into the mountains, and east into Ontario, Quebec, and the Atlantic provinces. The progress of this dramatic "invasion" has been carefully charted; for example, coyotes established themselves in Ontario about the turn of the century, in Quebec in the 1940s, and in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia in the 1970s. Most astonishing of all, coyotes have recently been discovered in western Newfoundland, apparently having crossed on the ice from Nova Scotia.

Feeding

Although primarily a flesh-eater, the coyote will eat just about anything available. Rabbits and hares are typically dietary staples, as are small rodents. Blueberries and other wild fruits are commonly eaten, in quantity, in summer and fall. Coyotes also eat insects, such as grasshoppers, when they become available. Where coyotes and wolves live near each other, coyotes scavenge from wolf kills. Carrion, flesh of dead animals, from livestock and other sources is important too, especially in winter. Coyotes commonly prey on deer fawns in spring and summer; however, they may also prey on adult-sized deer and other large hoofed mammals during certain snow conditions in winter. Coyotes prey on domestic sheep when they are available, and may take beef calves and domestic poultry, too.

Coyotes have flexible social behaviour and adjust their hunting methods to the prey size and food sources available. Coyotes often hunt small prey animals singly, whereas they hunt large prey and defend large carcasses in groups.

Breeding

Coyotes appear to be monogamous, and couples may remain together for several years. Both sexes can breed at one year of age under good conditions, although both sexes usually breed somewhat later in life. During the mating season, males solicit the females’ favours. The mating takes place mainly during February and March; gestation, or pregnancy, lasts from 60 to 63 days.

The coyote uses a den for the birth and early care of its cubs. It may be located at the base of a hollow tree or in a hole between rocks, but usually consists of a burrow in the soil. The coyote prefers to den on the banks of a stream or the slopes of a gorge and usually chooses a concealed spot. It often enlarges an abandoned marmot or badger burrow. The female may prepare alternative lodgings to enable her family to move to another refuge should trouble occur. Earth, pushed toward the entrance, is piled up onto a fan-shaped heap, which the animal skirts when going in or out. The same shelter may be used for several years.

Before the female gives birth, or “whelps,” the den is thoroughly cleaned. On average, she bears three to seven pups, covered with fine brown fur, whose eyes remain closed for the first eight or nine days.

The male prowls around and brings food to the entrance as long as the pups do not venture from the den. The adults remove waste as it accumulates. Weaning, or making the transition from the mother’s milk to other food, begins about one month after birth. The adults then feed the pups by regurgitating, or bringing up, half-digested food.

At about three weeks of age, the pups begin to romp around under the adults’ watchful supervision, first inside the shelter, then outside. If some enemy comes too close, the adult utters a special warning bark, then lures the enemy away.

Later, the adults teach the pups how to hunt. When fall comes, the young coyotes may leave their parents to claim their own territory. If there is an abundant food supply, pups may stay with the adults to form packs, or clans.

Conservation Chief among the coyote’s numerous foes are people. In some areas, 90 percent of the deaths of coyotes older than five months are caused by people, whether purposefully with guns, poison, and traps, or accidentally with vehicles and farm machinery. Wolves, black bears, mountain lions, and eagles all prey on the coyote. A Iynx can kill a coyote but will not attempt to do so unless the odds are in its favour.

Parasites and diseases can sometimes lead to death. Common are outbreaks of sarcoptic mange, an infestation by microscopic mites that causes thickening of the skin, loss of hair, and itching. Heartworm and hookworm are other common parasites of coyotes. Coyotes may also suffer from diseases such as distemper, canine hepatitis, rabies, and parvo virus.

From the time of European settlement, the coyote has been persecuted, because people have blamed it for preying on livestock. It is amazing that the coyote has thrived despite the organized attempts that were made to eradicate it in the first half of the twentieth century. Many governments offered bounties and funded extensive coyote control programs. Farmers often poisoned the carcasses of dead livestock with strychnine and left them in the back pasture for the "brush wolves" to find. A variety of devices and traps were also used to kill coyotes.

Although there are circumstances where predation by coyotes is still a serious problem for livestock producers, most people today realize that the coyote is not the worthless menace that it was once thought to be. The use of poison is now controlled by law. Bounties, or rewards, generally shown to be ineffective, are rare. Predator control is aimed at specific local problems. However, much of the research done on the coyote is still aimed at reducing predation on sheep. Also, respect for coyotes is required in urban areas, where they are increasingly at home. There are recent cases where these wild canines have attacked humans; children have been seriously injured.

Although it sometimes causes problems, the coyote has its rightful place in the animal kingdom. More and more people, including farmers, appreciate its value as a scavenger and a predator of rodents. The coyote’s economic importance and its role in nature should be considered in any evaluation of the animal. In areas occupied by people and their domestic animals, local control should be sought rather than a ban on the species as a whole.

Taken from Hinterland Who's Who: http://www.hww.ca/index_e.asp

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment, 1977, 1990. All rights reserved.

Catalogue number CW69-4/57-1990E

ISBN 0-660-13633-3

Text: D. Senécal

Revision: A. Todd and L. Carbyn, 1990

Photo: Tom W. Hall

Red Fox

Description

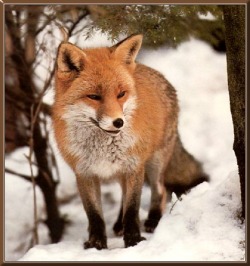

The red fox Vulpes vulpes is a small, dog-like mammal, with a sharp pointed face and ears, an agile and lightly built body, a coat of lustrous long fur, and a large bushy tail. Male foxes are slightly larger than females. Sizes vary somewhat between individuals and geographic locations—those in the north tend to be bigger. Adult foxes weigh between 3.6 and 6.8 kg and range in length from 90 to 112 cm, of which about one-third is tail.

Although "red fox" is the accepted common name for the species, not all members of the species are actually red. There are several common colour variations, two or more of which may occur within a single litter. The basic, and most common, colour is red in a variety of shades, with a faint darker red line running along the back and forming a cross from shoulder to shoulder on the saddle. Individuals commonly exhibit some or all of the following markings: black paws, black behind the ears, a faint black muzzle, white or light undersides and throat, a white tail tip, and white stockings.

Other common colours are brown and black. Red foxes that are browner and darker than most of their species and have a cross on the saddle that is dark and prominent are sometimes referred to as "cross foxes." Red foxes that are basically black with white-tipped guard hairs in varied amounts are known colloquially as "silver foxes." Silver foxes are particularly valued by the fur trade, and large numbers were selectively bred in captivity when fox fur clothing was popular.

Signs and sounds

Red foxes have a sharp bark, used when startled and to warn other foxes.

Habitat and habits Red foxes inhabit home ranges of 4 to 8 km2 around den sites. Pairs of adult foxes may separate during the winter, especially if hunting is poor, but they come together again in the later winter or early spring for breeding and denning. From autumn until March of the next year, the foxes take shelter in thickets and heavy bush, even during the coldest winter weather.

Red foxes have been called bold, cunning, and deceitful, particularly in children’s stories. In fact, they are shy, secretive, and nervous by disposition, and they appear to be very intelligent.

Unique characteristics

Young foxes travel widely during autumn seeking new territories. Young males have been traced as far as 250 km from their birth sites.

Red foxes have excellent eyesight, a keen sense of smell, and acute hearing, which help them greatly when hunting. The slight movement of an ear may be all that they need to locate a hidden rabbit. They can smell nests of young rabbits or eggs hidden by long grass. Sometimes they wait patiently for the sound of a mouse moving along its path in grass or snow and then pounce. At other times, hearing movement underground, they dig quickly and locate the prey by its scent.

Range

Foxes belong to the same family, the Canidae, as domestic dogs, coyotes, and grey wolves. Taxonomists, or experts who classify living organisms, once thought that the North American red fox was a different species from the smaller fox of southern Europe. It is now known, however, that they both belong to the same species. The range of Vulpes vulpes is continuous across Europe, Asia, and North America, and the species is expanding its range in North Africa and Australia, where it was introduced a century ago by British fox hunters.

Red foxes are one of Canada’s most widespread mammals, found in all provinces and territories. There are probably more red foxes in North America now than there were when Europeans began to arrive in the 16th century. Scientists believe that the range and numbers of the red fox expanded at that time because the pioneers created additional habitat for these small mammals by thinning the dense forests and killing many of the wolves that had kept fox numbers down.

Feeding

Probably red foxes eat more small mammals—voles, mice, lemmings, squirrels, hares, rabbits—than any other food, although they supplement this with a wide variety of other foods, including plants. Their diet changes with the seasons: they may eat mainly small mammals in fall and winter, augmented in spring with nesting waterfowl, especially on the prairies, and in summer with insects and berries. They have been seen feasting on eggs and chicks of colonies of nesting seabirds, and will take other birds, and their nestlings and eggs, when they can get them.

Red foxes have been known to eat and feed to their young lake trout weighing 1.5 to 3 kg, which they caught by leaping from the shore onto fish schooling in shallow water. They eat a wide variety of other items, including seal pups, beaver, reptiles, fruits of all sorts, and garbage. They will frequently bury or hide surplus food for later use, but other animals often find and use it first.

Foxes have a bad reputation as chicken thieves, and they will in fact invade poultry yards when it is safe and easy to do so. On farmlands, however, they more than compensate for the odd chicken by eating vast numbers of crop-destroying small mammals and insects, and they are now usually appreciated by farmers.

Red foxes hunt by smell, sight, and sound, as do most dogs. They have excellent eyesight, and the slight movement of an ear may be all that they need to locate a hidden rabbit. They have a keen sense of smell and acute hearing. They can smell nests of young rabbits or eggs hidden by long grass. Sometimes they wait patiently for the sound of a mouse moving along its path in grass or snow and then pounce. At other times, hearing movement underground, they dig quickly and locate the prey by its scent. They hunt mostly toward sunset, during the night, and in early morning.

Breeding

Dog foxes (males) and vixens (females) are usually, but not always, monogamous, or have only one mate. Two or more dogs often court a single vixen, and scientists have records of one den where three adult foxes tended a single litter of cubs. Home ranges around den sites are 4 to 8 km2 in size.

Foxes breed between late December (in warmer areas) and mid-March. After breeding, the foxes seek a suitable den, which is often an abandoned woodchuck burrow, but may also be the burrow of another mammal, a cave, a hollow log, a patch of dense bush, or a customized excavation under a barn or other structure. Small knolls in fields, streambanks, hedge and fence rows, and forest edges are favoured locations. Dens in earth are usually lined with dry material, such as grass or other leaves, to insulate the cubs from dampness and cold. Dens sometimes have more than one entrance, to permit escape from danger. They are often south-facing, with good visibility from the main entrance, and are usually in dry, sandy soil. An undisturbed den may be used by foxes for many years. A single pair of foxes may have two or more dens close to each other. They will sometimes move litters of pups from one den to another to escape danger, although at other times they do so for no apparent reason.

Pups are born from March through May. Litter size may range from one to 10 pups, but the average is five. The young are blind at birth, their eyes opening during their second week. Red foxes are patient, solicitous, and sometimes playful parents. The vixen takes great care of the very young cubs before their eyes are open and at this stage usually keeps the dog fox from entering the den, although he will hunt for the family. After the cubs’ eyes are open and they begin to crawl, the dog fox will relieve the vixen while she hunts.

At one month, the cubs are weaned, or have made the transition from their mother’s milk to other foods, and begin to play about the den entrance. Both parents hunt for themselves and bring back small game for the cubs to play with. In this way, the cubs learn the smell of the prey and how to eat it. For as long as two months the adults feed the cubs at the den site and train them to hunt, by stalking mice in the long grass. The cubs practise hunting under the eyes of the adults. When the young are able to feed themselves, usually at about three months of age, they leave the den site alone.

From autumn until March of the next year, the foxes bed down in thickets and heavy bush, even during the coldest winter weather. If successful in surviving their first winter and in finding a territory, the young foxes may breed the following spring. Pairs of adult foxes may separate during the winter, especially if hunting is poor, but they will come together again for breeding and denning.

Conservation

Humans are probably the most important predator of foxes. In the past, people considered red foxes pests, because they eat poultry, as well as game birds and small mammals that people also hunt, so governments offered rewards, or bounties, for killing foxes. The effectiveness of bounties in keeping down populations of mammals is doubtful, especially in the case of foxes, which produce five or more young every year. Fortunately, most people now recognize that the benefits that farmers derive from having foxes around far outweigh any damage that they do, and bounties have mostly been dropped. In recent years, too, long-haired fur has greatly increased in value, and red foxes are worth a lot of money to trappers.

Management of foxes in North America mainly consists of prohibiting hunting or trapping during the season when young are being raised, and until early winter when the fur is prime for trapping. Nuisance foxes are often destroyed on a local basis.

Wolves, coyotes, and dogs will chase and sometimes kill foxes when the opportunity presents itself. Interspecific strife with coyotes may be the reason that foxes usually occur close to human habitation in prairie areas. In some areas of British Columbia, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia, coyotes have been aggressively occupying new range for several decades and perhaps displacing red foxes. Bobcats, lynxes, and probably cougars may prey on red foxes. Other mammalian predators, such as bears, are likely not agile enough to catch foxes, except accidentally. Although eagles and large owls are capable of preying on foxes, there is little evidence that they do so.

Foxes have occasionally become a serious menace to public health, particularly in rural areas, when epidemics of rabies sweep through wild mammal populations. During epidemics, attempts are sometimes made to control the populations of foxes, raccoons, skunks, and other mammals that carry the disease. In Ontario, some advances have been made in the immunization of wild fox populations against rabies by dropping baits containing vaccine near den sites.

Because the disease is almost invariably fatal in humans once the symptoms are in evidence, rabid foxes should be avoided. When rabid, the normally shy and elusive red fox shows no fear of people, is often seen in daylight, and may foam at the mouth in advanced stages of the disease. Children should be warned to avoid bold or apparently friendly foxes. Rabies is transmitted through the bite of an infected animal. If a person is bitten, the wound should be washed immediately, and a doctor should be seen on an emergency basis. Rabies is a reportable disease and as such must be reported to the nearest veterinary authority, usually the District Veterinary Officer of the Animal Health Division, Food Production and Inspection Branch of the federal Department of Agriculture and Agri-Food. The brain of the animal involved should be submitted immediately to a Federal Veterinary Laboratory. Delay could result in the death of the person bitten.

Taken From Hinterland Who's Who http://www.hww.ca/hww2.asp?id=102

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment, 1993. All rights reserved.

Catalogue number CW69-4/5-1993E

ISBN 0-662-21022-0

Text: J.P. Kelsall

The Moose (alces alces)

Description

A bull moose in full spread of antlers is the most imposing beast in North America. It stands taller at the shoulder than the largest saddle horse. Big bulls weigh up to 600 kg in most of Canada; the giant Alaska-Yukon subspecies weighs as much as 800 kg. In fact, the moose is the largest member of the deer family, whose North American members also include elk (wapiti), white-tailed deer, mule deer, and caribou.

Moose Alces alces have long, slim legs that end in cloven, or divided, hooves often more than 18 cm long. The body is deep and massively muscled at the shoulders, giving the animal a humped appearance. It is slab-sided and low-rumped, with rather slender hindquarters and a stubby, well-haired tail. The head is heavy and compact, and the nose extends in a long, mournful-looking arch terminating in a long, flexible upper lip. The ears resemble a mule’s but are not quite as long. Most moose have a pendant of fur-covered skin, about 30 cm long, called a bell, hanging from the throat.

In colour the moose varies from dark brown, almost black, to reddish or greyish brown, with grey or white leg "stockings."

In late summer and autumn, a mature bull carries a large rack of antlers that may extend more than 180 cm between the widest tips but that are more likely to span between 120 and 150 cm. The heavy main beams broaden into large palms that are fringed with a series of spikes usually less than 30 cm long. The antlers are pale, sometimes almost white.

A bull calf may develop button antlers during its first year. The antlers begin growing in midsummer and during the period of growth are soft and spongy, with blood vessels running through them. They are covered with a velvety skin. By late August or early September the antlers are fully developed and are hard and bony. The velvet dries and the bulls rub it off against tree trunks.

Mature animals usually shed their antlers in November, but some younger bulls may carry theirs through the winter until April. Yearling bulls usually have spike antlers, and the antlers of two-year-olds are larger, usually flat at the ends. Moose grow antlers each summer and shed them each autumn.

Signs and Sounds

The voice of a newborn calf is a low grunt, but after a few days the calf develops a strident wail that sounds almost human. During the breeding season, or rut, the cow moose entices a mate with a nasal-toned bawling. The bull responds with a coughing bellow.

Habitat and Habits

Moose are found on the rocky, wooded hillsides of the western mountain ranges; along the margins of half a million lakes, muskegs, and streams of the great boreal forest; and even on the northern tundra and in the aspen parkland of the prairies.

Moose tolerate cold very well but suffer from heat. In summer, especially during fly season, moose often cool off in water for several hours each day. In fact, moose are quite at home in the water. They sometimes dive 5.5 m or more for plants growing on a lake or pond bottom. Moose have been known to swim 19 km. Of all North American deer, only the caribou is a more powerful swimmer. A moose calf is able to follow its mother on a long swim even while very young, occasionally resting its muzzle on the cow’s back for support.

Unique Characteristics

The eyesight of the moose is extremely poor, but its senses of smell and hearing compensate.

With their tremendous physical power and vitality, moose can travel over almost any terrain. Long legs carry them easily over deadfall trees or through snow that would stop a deer or wolf. Their cloven hooves and dewclaws spread widely to provide support when they wade through soft muskeg or snow. When frightened they may crash noisily through the underbrush, but in spite of their great size even full-grown, antlered bulls can move almost as silently as a cat through dense forest.

Before bedding down, a moose usually travels upwind for a time and then swings back in a partial circle. Thus predators following its track will have to approach from the windward direction. Skilled hunters know when to leave the track and work their way upwind to the hiding-place of their quarry.

Range

Moose are found in Canadian forests from the Alaska boundary to the eastern tip of Newfoundland and Labrador. It is estimated that there are between 500 000 and 1 million moose in Canada. Since the beginning of settlement in Canada there have been considerable shifts in the distribution of moose. They are found in many regions which had no moose in presettlement days. There are now large moose populations in north-central Ontario and in the southern part of British Columbia, where moose were previously unknown. They have only recently spread to the Quebec North Shore, north of the Gulf of St. Lawrence. The island of Newfoundland, which had never been occupied by moose, was "seeded" with a few pairs in the early 1900s and now has large populations. Moose are constantly spreading northwards through the sparse transition forest that extends to the open tundra

Feeding In summer the moose’s diet includes leaves, some upland plants, and water plants in great quantity where available. A large adult moose eats from 15 to 20 kg, green weight, of twigs each day in winter, and in summer eats from 25 to 30 kg of forage—twigs, leaves, shrubs, upland plants, and water plants. They also dip their heads under the surface of the water to feed on the lilies and other water plants.

In June and July, moose gather around salt licks, usually low-lying areas of stagnant, mineral-rich water. At that season, when they feed heavily on leaves and other lush plant growth, they seem to require the supplementary minerals that the salt licks provide. Moose drift to the willow-rich valleys or other areas where good forage exists close to forest cover.

During the winter months, moose live almost solely on twigs and shrubs such as balsam fir, poplar, red osier dogwood, birch, willow, and red and striped maples. Winter is a time of hunger for moose. They restrict their food intake and limit their activity to save energy. When food becomes scarce, as it often does toward spring, moose will strip bark from trees, especially poplars.

Before settlement, the large supplies of woody twigs needed by moose were provided by young forest regrowth in the wake of forest fires. Now that wildfire has been largely controlled, the moose’s source of food is often areas that are growing again after clear-cut logging.

Where predation and hunting are limited, moose numbers may increase to the point where food is inadequate. Under these conditions, many animals starve while all are malnourished and more likely to be killed by predators or disease. Concentrations of up to 135 animals per 10 km2 have been seen in Wells Grey Provincial Park in British Columbia.

Deer, elk, rabbits, and even beaver compete with the moose for food.

Breeding

The breeding season, or rut, begins in mid-September. Moose sometimes take more than one mate, but usually a bull stays with a particular cow during most of the breeding season.

A good food supply improves breeding success. On good range, more than 90 percent of the cows become pregnant and up to 30 percent bear twins. Very rarely, triplets are observed. However, when the food supply is poor, rates of pregnancy can drop to 50 percent, and the twinning rate almost to zero.

At birth a calf moose is a tiny, ungainly copy of its mother. If it is one of twins it may weigh 6 kg; if born singly, between 11 and 16 kg.

Calves are helpless at birth. The mother keeps them in seclusion for a couple of days, hidden from their many enemies in a thicket or on an island.

Of all North American big-game animals, the moose calf gains weight fastest. During the first month after birth it may gain more than half a kilogram a day, and later in the summer may begin to put on more than 2 kg a day for a time. At the age of only a few days a calf can outrun a human and swim readily.

Calves stay with the cow until she calves again the following spring. At that time she drives off her yearlings—no doubt a difficult experience for the "teenage" moose.

Conservation Bears and wolves prey on moose. Black and grizzly bears have been known to prey heavily on moose calves during the first few weeks of life, and grizzly bears can easily kill adult moose.

Throughout most wolf range in Canada, moose are the principal prey of wolves. Wolves kill many calves and take adult moose all year. Hunting healthy adult moose is a difficult and often dangerous business for wolves. The flailing hooves of a cornered moose frequently cause broken bones and even death, and only about one confrontation in 12 ends with the wolves successfully killing a moose. In winter, wolves usually hunt in packs. In deep crusted snow, or on smooth ice, a pack can easily bring down a moose. They usually run up beside their quarry and rip the tender flanks until the moose is weakened from loss of blood. In the end, wolves get almost every moose.

Wolverines also prey on moose calves occasionally. Where they coexist with moose, cougars take a substantial number of moose calves and yearlings. Few moose die of old age.

Ticks are common on moose, especially in late winter, and may weaken animals seriously both by sucking blood and by causing the affected moose to rub off much of its hair, causing substantial heat loss. Internal parasites such as the hydatid—a tiny tapeworm—affect moose, especially when lack of forage and a heavy tick infestation lower their resistance.

Another serious parasitic disease of moose is caused by the meningeal worm, so called because it attacks the meninges, or membranes, surrounding the brain and spinal cord. Meningeal worm is a parasite of white-tailed deer, which are adapted to it. However, in moose it is deadly, and there is a long history of moose dying in regions where the two species overlap.

Moose are an important economic resource in Canada. Moose hunting generates over $500 million in economic activity annually and provides large amounts of food for aboriginal and other rural people. Moose are a major element in the complex of wildlife attractions that draw visitors to parks and other wildlands to view and study nature.

Populations must be kept within the limits set by the food supply to prevent starvation, disease, and serious damage to vegetation. Foresters in areas that are overpopulated by moose find that the regeneration of forest trees is harmed significantly. This may seriously reduce future timber crops as well as the breeding habitat of songbirds that nest in deciduous shrubs.

Moose respond well to management of their habitat by logging or controlled burning if these activities maintain a diversity of open areas and patches of larger trees for cover. Today, moose management in Canada is soundly based on aerial counts, habitat inventories, and scientific studies of reproductive rates and calf survival. Moose have adapted well to human activities, and with appropriate management, they will always be part of the Canadian scene.

Taken from Hinterland Who's Who: http://www.hww.ca/index_e.asp

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment, 1997. All rights reserved.

Catalogue number: CW69-4/73-1997IN

Text: E.S. Telfer

Magpie (pica hudsonia)

Description

The black-billed magpie, a large bird in the crow family, is 45-60 cm (18-24 in) long and weighs 145-210 g (5.12-7.41 oz). They have a wingspan of 56-61 cm (22-24 in). Its bill, head, breast, and upper parts are black. The belly, shoulders and primary wing feathers are white. The inner wings are iridescent black glossed with green or purple. A long graduated iridescent black tail makes up half this bird’s total length. The male is slightly larger than the female; otherwise, the sexes look alike. Juveniles resemble adults but are duller with less iridescent upperparts.

The call is a harsh, chattering "wock, wock wock-a-wock, wock, pjur, weer, weer." Magpies are sociable birds and often roost in groups.

Distribution The Eurasian magpie is found across a vast range from northern Africa across Europe to Southeast Asia and Siberia. They are found in urban as well as rural areas.

Habitat Found in thickets in riparian areas, meadows, grasslands, sagebrush, and around people.

Food

Many types of insects and ground-dwelling invertebrates as well as carrion and small mammals and birds. They are capable of preying on animals as large as small rabbits. Lesser quantities of grain, acorns, seeds and fruit are also consumed. It forages primarily on the ground. Although it will take eggs and nestlings from other birds, these items make up only a tiny portion of its diet. The magpie will often land on large mammals (deer and moose) and eat the ticks found on them.

Magpies hoard food when it is abundant. Using their beak, they make holes in the ground throughout their territory in which to stash food. They cover the caches with a stone, leaf or grass.

Reproduction and Development

Adult magpies pair for life unless one dies, in which case the remaining individual finds another mate. Breeding begins in late March until early July. Magpies nest individually or in loose colonies, often toward the top of deciduous or evergreen trees or tall shrubs. Nests are built by both sexes using loose accumulations of branches, twigs and mud for the base and frame with grass, hair, roots and other soft materials as the lining. It is topped off with a loosely built dome of branches with a concealed entrance. The female incubates five to nine eggs (six or seven is most common) for 16-18 days. The male feeds the female throughout incubation. Chicks remain in the nest for three to four weeks after hatching and rely on their parents for food for up to two months after leaving the nest. Fledglings stay with their parents into the fall when they form other juveniles in loose flocks. A magpie will live an average of three to six years in the wild and begin breeding at age one or two. Some live much longer with the oldest recorded age being over 21 years.

Adaptations

They are able to hold food with their feet and peck it. Their bill has a sharp cutting edge which can be used for cutting flesh, picking fruit, or digging up invertebrates. They are sometimes known for opening wounds in large mammals.

Taken From:http://www.torontozoo.com/Animals/details.asp?AnimalId=546

Researched and collated by Sara Yeomans

Image courtesy of RSPB

The Muskrat (ondatra zibethicus)

Description

The muskrat Ondatra zibethicus is a fairly large rodent commonly found in the wetlands and waterways of North America. It has a rotund, paunchy appearance. The entire body, with the exception of the tail and feet, is covered with a rich, waterproof layer of fur. The short underfur is dense and silky, while the longer guard hairs are coarser and glossy. The colour ranges from dark brown on the head and back to a light greyish-brown on the belly. A full-grown animal weighs on the average about 1 kg but this varies considerably in various parts of North America. The length of the body from the tip of the nose to the end of the tail is usually about 50 cm. The tail is slender, flattened vertically and up to about 25 cm long. It is covered with a scaly skin that protects it from physical damage.

Only a minimal amount of hair grows on the feet. The hand-like front feet are used in building lodges, holding food, and digging burrows and channels. Although the larger hind feet are used in swimming, they are not webbed like those of the beaver and otter. Instead, the four long toes of each foot have a fringe of specialized hairs along each side, giving the foot a paddle-like effect. The rather small ears are usually completely hidden by the long fur. The four chisel-like front teeth (two upper and two lower incisors), each up to 2 cm long, are used in cutting stems and roots of plants.

The muskrat’s name is derived from the fact that the animal has two special musk glands—also called anal glands—situated beneath the skin in the region of the anus. These glands enlarge during the breeding season and produce a yellowish, musky-smelling substance that is deposited at stations along travel routes used by muskrats. Common sites of deposition are "toilets," bases of lodges, and conspicuous points of land. The biology of musk glands has not been studied extensively, but the odour produced is believed to be a means of communication among muskrats, particularly during the breeding season.

Habitat and Habits

Muskrats typically live in freshwater marshes, marshy areas of lakes, and slow-moving streams. The water must be deep enough so that it will not freeze to the bottom during the winter, but shallow enough to permit growth of aquatic vegetation—ideally between 1 and 2 m. Areas with good growths of bulrushes, cattails, pondweeds, or sedges are preferred.

Compact mounds of partially dried and decayed plant material can frequently be seen scattered among the cattails and bulrushes. These dead-looking heaps are homes of the muskrat. Bulrushes and cattails are most important, particularly in lakes. As well as being eaten, they are used as building material in the construction of lodges and feeding stations, and as shelter from winds and wave action. In northern regions, horsetails can be important in muskrat habitat.

If bulrushes or cattails are not available, muskrats dig burrows in firm banks of mossy soil or clay. Because muskrats require easy access to deep water, water depths must increase fairly rapidly from the shore where burrows are situated. This provides muskrats with an opportunity to escape from predators, and with a food supply under the ice during the winter.

Some people refer to muskrats as "house rats" and "bank rats" because the animals build lodges in certain areas and bank burrows in others. Often, these names are used in a way that suggests that these two "types" of muskrats possess inherited biological differences. This is not the case. The type of habitation used is simply a response to local conditions.

With the shortening of days and the coming of colder weather in September, preparations for winter begin. The fall is spent building and reinforcing lodges for winter occupancy, and, in some regions, storing food for winter use. Lodge building behaviour is an extremely important aspect of the ecology of muskrats. The lodge permits them to live in areas surrounded by water, far away from dry land. It protects them from enemies and gives them shelter from the weather.

A muskrat builds a lodge by first heaping plant material and mud to form a mound. A burrow is then dug into the mound from below the water level, and a chamber is fashioned at the core of the mound. Later, the walls of the lodge are reinforced from the outside with more plants and mud. A simple lodge of this type is about 0.5 to 1 m high and 0.5 to 1 m in diameter. It contains only one chamber and has one or two plunge holes, or exit burrows. More complex lodges, containing several separate chambers and plunge holes, may be up to 1.5 m high and 1.8 m in diameter.

Shortly after freeze-up, muskrats chew holes through the ice in bays and channels up to 90 m away from the lodge to create "push-ups." After an opening has been created, plant material and mud are used to make a roof over it, resulting in a miniature lodge. Typically there is just enough room for one muskrat in the push-up. It is used as a resting place during underwater forays, and as a feeding station.

The winter is a period of relative inactivity. The muskrat is safe from the cold and from most predators. It spends most of its time sleeping and feeding until breeding activities begin after spring break-up.

The muskrat is well adapted to a semi-aquatic life style. Although fully functional on land, it has evolved characteristics that make it at home in the water. At three weeks of age it is a capable swimmer and diver. As an adult, it swims effortlessly and can do so for long periods of time. This ability is greatly facilitated by the buoyant qualities of the thick waterproof fur. When swimming on the surface, the muskrat tucks its front feet slightly forward against the upper chest while using the back feet in alternate strokes to propel the body. The tail is used at most as a rudder. When the muskrat is swimming under water, however, the sculling action of the tail probably provides as much propulsive force as do the hind feet.

In the late evening during ice-free periods of the year, muskrats can be seen swimming, sitting at feeding stations such as logs or points of land, and busily improving lodges.

Although the muskrat builds lodges near the water and is an accomplished swimmer, it is not a close relative of the beaver, as is sometimes thought. Nor is it a true rat. Instead, it is basically a large field mouse that has adapted to life in and around water.

Unique characteristics

The muskrat, together with the beaver and several other mammals, is capable of remaining submerged up to 15 minutes if in a relaxed state. Non-aquatic mammals cannot do this because they need a constant supply of oxygen and must continually expel carbon dioxide. The muskrat is able to partially overcome this problem by reducing its heart rate and relaxing its muscles when submerged; this reduces the rate at which oxygen is used. Also, it stores a supply of oxygen in its muscles for use during a dive and is less sensitive to high carbon dioxide levels in the blood than are non-diving mammals. This ability for extended dives is important in escaping enemies, digging channels and burrows, cutting submerged stems and roots, and travelling long distances under the ice.

The muskrat’s front teeth are especially modified for underwater chewing. Non-aquatic mammals such as dogs or humans would have great difficulty in trying to chew on a large object under water, because water would enter the mouth, throat, and nasal passages. This problem has been overcome in the muskrat through the evolution of incisors, or cutting teeth, that protrude ahead of the cheeks and of lips that can close behind the teeth. This adaptation permits the muskrat (and the beaver) to chew on stems and roots under water "with its mouth closed."

Range

The muskrat is more widely distributed in North America than almost any other mammal and in this respect is a very successful species. It is found from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Gulf of Mexico in the south and from the Pacific Ocean in the west to the Atlantic Ocean in the east. This broad distribution is closely related to the muskrat’s use of aquatic environments, which are common in North America. Human activities in North America during the last two centuries have not significantly affected the distribution of muskrats. In some cases, however, the draining of marshes or swamps for agricultural or other purposes has completely exterminated local populations. In others, the building of irrigation ditches and canals has increased populations.

Until the early part of this century, muskrats occurred only in North America. In about 1905, they were introduced to Europe, where they quickly established themselves as permanent residents. They spread northward and eastward, and today are common in Europe and northern Asia.

Feeding Of all plants available in marshes, cattails are most preferred as a food item. However, muskrats appear to thrive equally well on a diet of bulrushes, horsetails, or pondweeds, the last two constituting the basis of the diet in northern latitudes. They also eat a variety of other plants, including sedges, wild rice, and willows.

During the winter a thick layer of ice restricts the muskrat to the interior of the lodge or burrow and the watery environment beneath the ice. The animal’s highly developed diving abilities and its use of push-ups become critical in procuring food under those conditions. It covers considerable distances under the ice searching for food. When the muskrat reaches a feeding area it chews off portions of plants and carries them to the nearest push-up, where it eats. This foraging activity under perhaps a metre of ice and snow, in ice-cold water and almost total darkness, is truly a remarkable feat.

When their normal food items are scarce or unavailable, and food of animal origin is abundant, muskrats are known to be highly carnivorous, or meat-eating. Under these circumstances muskrats most commonly consume animals such as fish, frogs, and clams. However, muskrats rarely do well on this type of diet and consuming such foods is generally taken to be evidence of hard times.

Breeding

Mating activity occurs immediately following spring break-up in March, April, or May. Mating pairs do not form lasting family ties; instead, the muskrat appears to be promiscuous, or have many mates. Males compete fiercely for females. The birth of the litter, containing five to 10 young, occurs less than a month after the female has been mated. The same female normally has another litter a month after the first, and sometimes yet another a month after the second.

The young at birth are blind, hairless, and almost completely helpless, but they develop rapidly. They are covered with thin fur at the end of the first week, their eyes open at the end of the second week, and they normally begin leaving the lodge on short trips at about two to three weeks of age. Weaning, or making the transition from the mother’s milk to other foods, occurs at about three weeks, and juveniles are essentially independent of their parents at six weeks.

Breeding continues throughout the summer, with the last litters born about August. Food is plentiful during the summer and the young grow rapidly.

Few rodents live to old age; they are usually killed by other animals while still quite young, or they die accidentally. The limited information available suggests that muskrats become old at three or four years of age. When they reach this age, they lose much of their natural alertness and fall easy prey to mink, foxes, and other predators.

Conservation

The muskrat is a vicious fighter when provoked. It stands its ground courageously if an escape route to deep water is not available and can inflict considerable damage on an attacker with its long incisors, or cutting teeth. In spite of this, it is often preyed upon by other species. The mink occupies much of the same habitat as muskrats and can be the cause of heavy mortality among juveniles under certain conditions. Mink use the same burrow systems, dig into muskrat lodges, and may enter lodges through plunge holes. The snapping turtle and the northern pike also inhabit marshes and prey on the muskrat. When muskrats wander on dry land in search of new habitat, they are subject to predation by members of the dog family—wolves, coyotes, foxes, and domestic dogs—as well as by typical predators such as badgers, wolverines, fishers, racoons, and lynx.

The muskrat has long been hunted by humans, probably the major enemy or predator of this species. Prior to the colonization of North America by Europeans, it was hunted occasionally for food. With the coming of the early settlers and the introduction of guns and traps, the muskrat was hunted intensively for its fur. This activity has persisted to the present day—muskrat fur is still in demand. Also, the muskrat is still used as food by people in some parts of North America.

Muskrats, like many other wildlife species, show large fluctuations in numbers that follow what appears to be a regular pattern. In the case of the muskrat, numbers decrease drastically about every seven to 10 years. At such times, few or no muskrats can be found where two or three years earlier there had been thousands. These catastrophes are often blamed on predators or on over-trapping. However, scientists do not believe that these are the real causes. Instead, for some as-yet-unknown reason, the health of individuals deteriorates, causing widespread death and reproductive failure. Reproductive and death rates return to normal one or two years following such a population decline, leading to an increase in muskrat numbers once more.

The muskrat contributes more to the total combined income of North American trappers than any other mammal. Because of its important role in the trapping industry, it has been studied extensively. The first major studies were conducted by the Canadian Wildlife Service on the Mackenzie River Delta in the far north and the Athabasca–Peace Delta in northern Alberta during the late 1940s. A thorough understanding of habitat requirements, food habits, reproduction, longevity, causes of mortality, long-term changes in numbers, and the effect of weather on all these factors is essential to put management procedures on a sound scientific basis. The single most important contribution to our understanding of the biology and ecology of the muskrat was Paul Errington’s Muskrat Populations (1963), which combined the results of years of study by the author with information on the muskrat throughout North America. More recent studies in eastern Canada and central and eastern United States have augmented what is now a comprehensive body of knowledge on the dynamics and management of muskrat populations.

There are two major methods of managing muskrat populations: the first is to improve habitat, and the second is to regulate the commercial harvest by trappers. The most common method of improving habitat is to regulate water levels between about 1 and 2 m of depth over large areas by building dams at strategic points in lake outlets and streams. Sometimes this occurs as a natural side effect of beaver dams.

Regulation of commercial harvest is based on current population sizes and future population trends. Usually the harvest is maintained at the highest possible level that will not adversely affect population sizes and harvests in future years.

The future of the muskrat in Canada is bright. In spite of heavy trapping pressure, the draining of marshes for agricultural purposes, and unprecedented industrial activity, the species has never been endangered in Canada. Indeed, population numbers today are probably almost as high as they were a thousand years ago.

Taken from Hinterland Who's Who: http://www.hww.ca/index_e.asp

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment, 1974, 1987. All rights reserved.

Catalogue number CW69-4/52

Text: M. Aleksiuk

Revision: G. Parker, 1986

Snowshoe Hare (lepus americanus)

Description

The snowshoe hare Lepus americanus, one of our commonest forest mammals, is found only in North America. It is shy and secretive, often undetected in summer, but its distinctive tracks and well-used trails (“runways” or “leads”) become conspicuous with the first snowfall.

Well-adapted to its environment, the snowshoe hare travels on large, generously furred hind feet, which allow it to move easily over the snow. In soft snow, the four long toes of each foot are spread widely, increasing the size of these “snowshoes” still more. A seasonal variation in fur colour is another remarkable adaptation: from grey-brown in summer, the fur becomes almost pure white in midwinter. The coat is composed of three layers: the dense, silky slate-grey underfur; longer, buff-tipped hairs; and the long coarser guard hairs. The alteration of the coat colour, brought about by a gradual shedding and replacement of the outer guard hairs twice yearly, is triggered by seasonal changes in day length.

The snowshoe hare moults twice a year, beginning in August or September and in March or April. Generally, the hind feet retain patches of white fur into the summer. In the humid coastal zones of southwestern British Columbia, Washington, and Oregon, where snow is infrequent, snowshoe hares remain brown throughout the year.

The snowshoe hare’s ears are smaller than most hares’. The ears contain many veins, which help to regulate body temperature; for example, desert hares have very large ears with almost no fur, so the blood can cool in the slightest breeze. Because snowshoe hares live in cold environments, they do not need such big ears to help lower their body temperatures.

Female snowshoe hares are often slightly larger than males. Adult snowshoe hares typically weigh 1.2 to 1.6 kg; the hares are usually heaviest during the peak and early decline of the population cycle.

Signs and sounds

Snowshoe hares are generally silent, but they can show annoyance by snorting. On the rare occasions when they are caught, they utter a high-pitched squeal, which sometimes causes surprised hunters to drop them. During the breeding season, bucks and does (males and females) make a kind of a clicking noise to each other. Does also use this sound to call their young to them for nursing.

Habitat and Habits

The snowshoe hare lives in boreal forest, the northernmost forest in the Northern Hemisphere. Its range also extends into mountains in the United States. In eastern Canada and mountainous areas, the forest is predominantly coniferous (spruce and fir), whereas over large expanses of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba, the forest is mainly deciduous (aspen and balsam poplar). Snowshoe hares use many forest types. Overall, they prefer areas with a dense understory, or layer of plants below the main canopy of the forest, whether that is formed by young trees or by tall shrubs. This cover helps to protect them from predators and provide them with food.

The home range of a snowshoe hare—the area within which it normally lives—is approximately 6 to 10 ha. Within that range, the hare has an intricate network of trails that criss-cross its territory. These trails, which take the hares between feeding and resting places, are well-travelled, both by the hares and by other species, like squirrels, porcupines, and skunks. Major runways follow the same routes in summer and in winter, and the snowshoe hares keep the trails well-maintained, quickly clipping off stems and leaves which begin to block the runways; they may need these routes to escape predators.

Snowshoe hares are very active between sundown and dawn, and they remain active all winter. Rain, snow, or wind often markedly reduce the hares’ activity. During the daytime, the snowshoe hare rests quietly in sheltered spots called “forms,” under a bush, stump, or log. It dozes fitfully and grooms itself by licking its fur, but it is always alert.

If it is threatened, the snowshoe hare may freeze to take advantage of its camouflaging coloration, or it may flee. Snowshoe hares younger than two weeks, which cannot yet move swiftly, remain immobile. Older snowshoe hares are likely to flee; often, they will see predators before being seen, and can move away undetected. They travel by bounding, sometimes covering 3 m at a time, and they can travel as fast as 45 km/h. This is one way in which hares differ from rabbits—while hares are likely to run to escape predators, rabbits will dash to underground warrens and hide in them; hares rarely go underground. Linked to this difference in behaviour are some anatomical differences, including the hare’s bigger heart, which helps it run.

Unique characteristics

The spectacular cyclic fluctuations of snowshoe hare populations are well known. These remarkably regular fluctuations, which are about 10 years long, can be traced back over 200 years in the fur records of the Hudson’s Bay Company. At the population peak, hares can be extremely abundant, reaching densities of 500 to 600 hares per square kilometre. Population peaks occur roughly at about the same time, throughout the snowshoe hare’s range, although the timing of peaks may vary by one to three years between regions. Population declines are largely caused by predation.

Distribution of the snowshoe hare

The snowshoe hare is found in every province and territory in Canada. It lives in the boreal forest and the southern extensions of this forest, along the Appalachian Mountains in the east and the Rocky and Cascade mountains in the west. The snowshoe hare is found as far south as North Carolina, New Mexico, and California. To the north, it reaches the Arctic Ocean in the willow swales, or depressions, of the Mackenzie River delta.

Feeding Back to top

Snowshoe hares consume a variety of herbaceous plants during the summer, including species like vetch, strawberry, fireweed, lupine, bluebell, and some grasses. They also eat many leaves from shrubs. Their winter diet consists of small twigs, buds, and bark from many coniferous and deciduous species. Their geographic range is so large that snowshoe hares in different regions may have completely different diets, depending entirely on the local forest type.

The hares often stand to clip shrubs up to 45 cm from the ground, and as the snow builds, they can clip higher and higher. In peak population years, snowshoe hares may kill saplings and shrubs by girdling, or taking rings of bark from the plants. Snowshoe hares occasionally scavenge meat from the carcasses of other animals. Most small herbivores, including mice, voles, and rabbits, will eat meat occasionally if it is available—good sources of protein are rare in plant foods, so most herbivores eat meat when they can.

Breeding Back to top

Snowshoe hares start breeding during the spring after their birth. The breeding season begins about mid-March with courtship parades. Each female is receptive to males for about 24 hours, first in March, and then the day after giving birth to each litter—two to four times during the summer. During that day, females and males often travel together while foraging, with interludes of active chasing and jumping over each other. Females often breed with several males.

The first litter is usually born in May after a 36-day gestation period. Litters contain anywhere from one to 13 young. The first litter in each summer is usually the smallest, with three to four young. The second litter is often the largest, with an average size of four to seven young.

Snowshoe hares are born fully furred with their eyes open, and they are capable of hopping about almost immediately. Such precociousness is characteristic of hares in general, and is in marked contrast to young rabbits, which are born naked and blind. Young snowshoe hares nurse only once a day, usually in the evening, and are self-supporting at three to four weeks of age. They weigh between 45 and 75 g at birth, gain 450 g within a month, and reach the average adult weight of 1.4 kg by five months.

Conservation Back to top

The snowshoe hare suffers from many diseases—viral, bacterial, and parasitic. It is also the victim of many predators: among the most common are the Canada lynx, red fox, coyote, mink, Great Horned Owl, and Northern Goshawk. Snowshoe hares younger than two weeks of age are killed primarily by red squirrels and ground squirrels. Between 1 percent and 40 percent of snowshoe hares survive each year; the rate varies with the 10-year population cycle. Although snowshoe hares can live to six years old, very few survive that long; they are extremely lucky if they make it to their second summer of breeding.

The snowshoe hare is the most important small game animal in Canada. It is a mainstay in larders of Aboriginal peoples, and on the island of Newfoundland, where it was introduced in the 1870s, thousands of snowshoe hares are snared each year for meat, and they are sold in markets. In the Prairie provinces, on the other hand, non-Aboriginals are reluctant to eat hares. This prejudice apparently stems from the widespread belief that the animals harbour a mysterious disease which causes their cyclic decline.

As one of the dominant herbivores and key prey species within the boreal forest, the snowshoe hare contributes to this ecosystem’s diversity. Because they are a frequent prey item, snowshoe hares are critical to maintaining the food web in our forests; indeed, research in Yukon has demonstrated that the snowshoe hare may be a keystone, or central, species. Logging, fire, habitat conversion, and global warming are changing the distribution and quality of forested habitats. The 10-year cycle in snowshoe hares and their predators is a unique, dominant, and large-scale pattern in Canadian forests, and we do not know how habitat alteration will affect it.

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment, 1974, 1980, 2002, 2005. All rights reserved.

Catalogue number CW69-4/44-2003E-IN

ISBN 0-662-34257-7

Text: L.B. Keith

Revision: Karen E. Hodges, 2002

Editing: Maureen Kavanagh, 2002, 2005

Photo: Gordon Court